Past literature has found that Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely to be stopped by the police, convicted of a crime, denied bail, and issued a lengthy prison sentence. In light of these disparities, research has developed to determine whether these outcomes are influenced by discrimination on the part of police officers, judges, and other criminal justice agents, and to what extent discrimination impacts criminal justice outcomes.

In May 2021, Dartmouth assistant professor Dr. Steve Mello published his own promising contribution to the conversation. Current methods for addressing these questions focus on detecting the presence of racial discrimination on average ––for instance, in a police department or at the county level–– but Mello's research aims to add to this existing literature by identifying discrimination at the level of individual police officers. Namely, Mello's paper titled "A Few Bad Apples? Racial Bias in Policing" investigates whether or not officers discriminate when enforcing punishments for speeding.

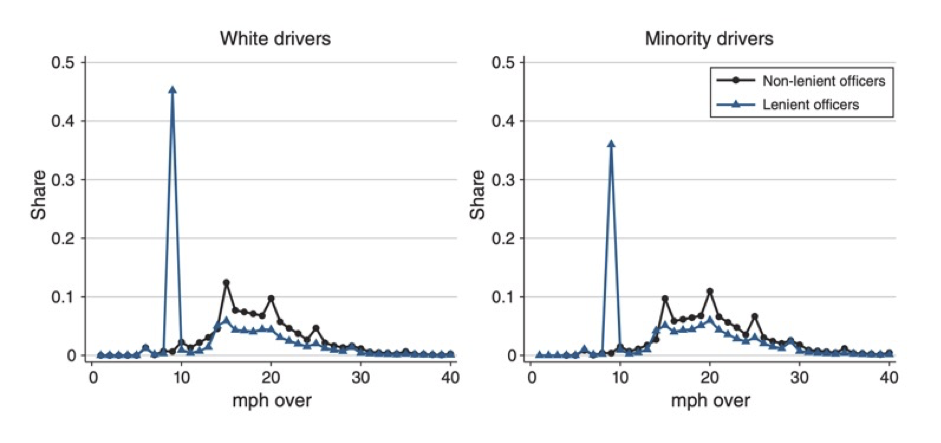

Figure 1: Minority drivers are less likely to receive a discounted speed on their ticket

Note: This figure depicts two density functions that have the same total area of 1.0 beneath them. Each density function shows the distribution in ticketed speeds by non-lenient and lenient officers for white and minority drivers, respectively.

Discrimination in enforcing speeding tickets is based on officer lenience. In many states, the punishment for speeding becomes increasingly harsh as the driver's ticketed speed increases. Because of this, officers who choose to exercise lenience may reduce, or discount, the written speed on a driver's ticket to a speed right below an increase in the fine. Mello's study investigates how the tendency to make allowances for speeding varies across driver race. In his research, he finds that minorities are significantly less likely to be written down for a speed just below the fine point, and thus less likely to be discounted on their speeding rate. Figure 1 shows the distribution in ticketed speeds for white and minority drivers. The difference in the size of the spikes at 9 mph for lenient officers indicates that a larger share of white drivers are ticketed at 9 mph, just below an increase in the fine. Using this "bunching" around the fine point, it is determined that minority drivers are significantly less likely to experience officer lenience for a speed ticket.

The results of the study are derived from traffic policing data by the Florida Highway Patrol between 2005 and 2015. Using a bunching estimator in a difference-in-differences framework to compare non-lenient officers with lenient officers, Mello finds that minority drivers are significantly less likely to be given a discounted speed on their ticket (see figure 1). On net, he attributes 82 percent of the racial gap in discounting to discrimination by patrol officers. Additionally, by disaggregating this difference to the individual police officer, it is estimated that 42 percent of officers practice discrimination. As a potential solution for the disparity in discounting rates for speeding tickets, Mello proposes reassigning officers across locations based on their lenience.

Discrimination and officer leniency

Figure 2: Officers vary significantly in their level of lenience

[[{"fid":"12811","view_mode":"dart_wysiwyg_width_590","fields":{"alt":"Implicit Bias in Policing Figure 2","class":"media-element file-dart-wysiwyg-width-590","data-delta":"2","format":"dart_wysiwyg_width_590","alignment":"center","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Implicit Bias in Policing Figure 2","field_file_caption[und][0][value]":"","external_url":"","field_file_caption[und][0][format]":"plain_text"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"2":{"alt":"Implicit Bias in Policing Figure 2","class":"media-element file-dart-wysiwyg-width-590","data-delta":"2","format":"dart_wysiwyg_width_590","alignment":"center","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Implicit Bias in Policing Figure 2","field_file_caption[und][0][value]":"","external_url":""}},"attributes":{"alt":"Implicit Bias in Policing Figure 2","class":"media-element file-dart-wysiwyg-width-590 media-wysiwyg-align-center","data-delta":"2"}}]]

Note: This figure shows the heterogeneity (variedness) in lenience across officers. Panel A plots the officer-level distribution of lenience. Panel B plots the share of tickets in each county and shift that is written by non-lenient officers. The lower two panels confirm that officers are persistent in their level of lenience across time and location.

Officers in the Florida Highway Patrol have a plausible motivation to exercise lenience. In particular, officers may have a promotion incentive to write a certain number of tickets because the number of tickets they write appears on their performance evaluations. In this environment, officers may be encouraged to write more tickets but do not seem to face an incentive to write harsher tickets. This environment is ideal for Mello's research design, in which the final sample included 2,122,555 citations issued by 1,851 officers. The sample does not include data for traffic stops in which no citation was given.

The study finds that 42 percent of officers practice discrimination when discounting speeding tickets. A highly discriminatory officer ––one belonging to the 90th percentile of discrimination–– is more than 10 percentage points more likely to discount a white driver than a minority driver. The modal officer, however, practices no discrimination according to the results of this study. Indeed, the level of lenience exercised across officers is significantly varied, and most appear to exhibit very little lenience (see figure 2).

It is possible that there exists a gap in which minority drivers are more likely to drive over the speed limit. To rule out this possibility, the researchers observed the speed distribution of non-lenient officers, who exhibit no discounting behavior. From this distribution of non-lenient officers, the study finds that minority drivers tend to drive at slightly faster speeds when stopped. However, since this racial gap in speeding was found to be minimal, the study concludes that discrimination plays some part in the disparity in discounting rates between white drivers and minority drivers.

The source of discrimination

Past literature has found that implicit bias is the source of discrimination in many instances. In these cases, the individual is not aware of their own biases. Because the level of discrimination of an average officer is relatively small in magnitude, the discrimination of an average officer is consistent with a theory of implicit bias. It is certainly possible, however, that the most discriminatory officers are aware of the biases influencing their treatment of white and minority drivers. The results of this study are more consistent with a taste-based rather than statistical explanation of discrimination. In other words, discrimination by officers appears to be influenced by their "preference" for certain races, rather than the pursuit of deterrence or fewer court contestations.

Some groups are more likely to act in a discriminatory manner than others. For instance, white officers are more likely to be discriminatory against minority drivers. Black officers exhibit no discrimination on average, and female officers are less likely to be discriminatory on average. However, it should be noted that minority officers tend to be placed in troops in which all officers are less lenient, driving part of the disparity in discrimination across officer race.

How can we address this disparity?

The study examines a few potential solutions and evaluates their effectiveness at reducing the disparity in discounting rates. Firstly, Mello investigates the effects of policies directly targeting discrimination in the police force. These policies include measures such as firing the most discriminatory officers or increasing the presence of minority or female officers. The study finds that these policies do reduce the disparity in discounting rates, but the reduction from this approach is limited. In particular, after firing the most discriminatory officers, minority drivers tend to receive increased exposure to officers who, while less discriminatory, are also less lenient overall.

If able to be implemented, the most effective approach suggested by the paper is reassigning officers across counties such that minorities are exposed to more lenient officers. This approach removes nearly all of the discounting gap between white and minority drivers, reducing the treatment gap by 91 percent.

However, there are some caveats that could render this approach less effective. For instance, officers may change their leniency behavior in response to being reassigned counties. In this scenario, officers may become less lenient in response to being placed in minority-majority counties or more lenient in response to being placed in white-majority counties. Additionally, there is a risk that increased lenience will lead to increased speeding. Though this may still reduce the discounting gap, it is an unfavorable result due to the increased traffic risk associated with more frequent speeding. These risks should be taken into consideration when designing policies or initiatives targeted toward reducing the discounting gap. Regardless, policies targeting officer lenience seem to be the most effective for reducing the disparity in discounting rates between white and minority drivers.

Read the full paper in the American Economic Review:

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20181607

For an interview with Dr. Steve Mello:

https://www.aeaweb.org/research/racial-bias-policing-florida

For additional information on the difference-in-differences method:

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

For additional literature on the economics of crime and discrimination:

"Racial Bias in Bail Decisions," David Arnold, Will Dobbie & Crystal S. Yang, 2017: https://www.nber.org/papers/w23421

"An Economic Analysis of Black-White Disparities in NYPD's Stop and Frisk Program," Decio Coviello & Nicola Persico, 2013: https://www.nber.org/papers/w18803

"The Impact of Jury Race in Criminal Trials," Shamena Anwar, Patrick Bayer & Randi Hjalmarsson, 2010: https://www.nber.org/papers/w16366

"Racial Disparity in Federal Criminal Sentences," Marit Rehavi, Sonja Starr, 2014: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/1414/