Over the past three decades, cities across the United States have spent more than $6 billion on initiatives to demolish public housing in high-poverty areas and provide tens of thousands of displaced residents with housing vouchers (US Government Accountability Office 2007). In his paper "Moved to Opportunity: The Long-Run Effects of Public Housing Demolition on Children," Dr. Eric Chyn investigates how the public housing demolitions in Chicago during the 1990s affected the young adult outcomes of children from households that relocated. He accomplishes this by comparing the young adult outcomes of displaced children to their peers who lived in nearby public housing that was not demolished.

According to Chyn's study, there are significant benefits to relocating children from public housing. Displaced children are 9 percent more likely to be employed as adults and have 16 percent higher annual earnings relative to their peers who grew up in public housing that was not demolished. Additionally, the paper finds positive impacts on schooling and criminal activity as well: all children who were displaced have 14 percent fewer arrests for violent crimes in the years following demolition, and those displaced when relatively young are 8 percent less likely to drop out of high school.

The results of this paper contribute to a growing body of literature on the long-term effects of relocation from public housing. From a policymaking standpoint, this paper provides evidence that the relocation of low-income families from distressed public housing positively impacts adult outcomes in labor market, criminal, and schooling activity, and yields net gains for government budgets in the process.

History and Background of Public Housing Demolition in Chicago

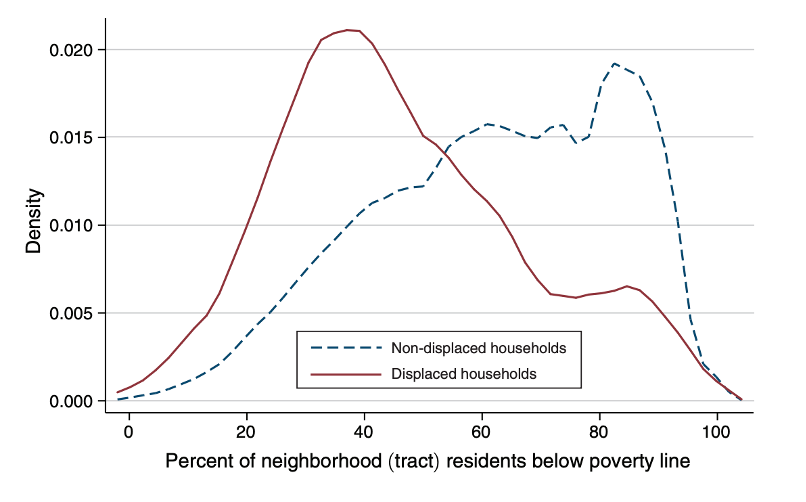

Figure 1: A large share of displaced residents relocate to neighborhoods with lower poverty rates.

Notes: The figure shows statistics for the average neighborhood poverty rate for each household in the sample, with two distributions for the displaced and non-displaced households. The average is computed over all post-demolition neighborhoods for the household regardless of whether a child is still present.

Chyn's paper centers on the case of Chicago where the housing authority began reducing its stock of public housing during the 1990s. The demolition of public housing in Chicago during the 1990s began as a reaction to serious housing management problems. By the end of the 1980s, chronic infrastructure problems plagued much of the public housing stock, which had been built poorly during the 1950s and 1960s. Furthermore, a large share of public housing residents lived below the poverty line, and some policymakers believed that relocation could move residents towards better socio-economic opportunities in lower-poverty areas.

Data and Empirical Strategy

The data used to test whether demolition has an impact on long-run outcomes of children is drawn from multiple administrative sources. Specifically, Chyn combines building records from the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) and social assistance case files from the Illinois Department of Human Services to create a sample of children who lived in public housing and were affected by demolition during the 1990s. Using this data, Chyn's paper studies the impact of demolition by exploiting the fact that the CHA selected a limited number of buildings for demolition within each public housing area during the 1990s. Specifically, his research design compared the young adult outcomes of displaced and non-displaced children from the same public housing development. Because these two groups of children and their households were similar before demolition, differences in later-life outcomes can be attributed to neighborhood relocation.

Benefits to Relocation

The paper observes significant benefits to relocating children of any age from public housing. In particular, one result is that displaced children grow up to have notably better labor market outcomes. Displaced children are 9 percent more likely to be employed as adults relative to their non-displaced peers. Furthermore, displaced children have $602 in higher annual earnings, equivalent to an increase of 16 percent relative to their non-displaced counterparts. In addition, the paper finds that displaced children are 8 percent less likely to drop out of high school and have 14 percent fewer arrests for violent crimes in the years following demolition.

The effects of demolition on employment, earnings, and arrest rates differ based on subgroup. For instance, the positive impact detected for the full sample seems to be mainly driven by girls. Relative to their non-displaced peers, girls are 13 percent more likely to be employed and have 18 percent higher annual earnings. The corresponding effects for boys are less precisely estimated, although the estimates for all outcomes are positive. However, the decrease in the rate of arrest for violent crimes seems to be larger for boys. In line with evidence from other recent studies of relocation, Chyn finds that there are larger positive impacts for children who were relatively young when they moved.

Policymakers may be concerned about designing housing policy that yields a net gain for government budgets. Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that a child who moves out of public housing due to demolition earns $45,000 more in their lifetime. The increased tax revenue associated with this earnings gain exceeds the average cost of relocating public housing residents, which suggests that efforts to improve the long-run outcomes of disadvantaged children will yield net gains for government budgets.

Concluding thoughts

At the time of the paper's publishing in 2018, research on the long-term effects of public housing demolition was limited. One notable study, done by Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz, focused on the effects of exposure to better neighborhoods through the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) experiment. Their 2016 study found no evidence of benefits for children who were older when their family moved to a low-poverty area through MTO. Chyn's research, done in the demolition context, adds to prior literature such as the 2016 study by providing additional evidence on the childhood exposure effects of neighborhood poverty and showing that even involuntary displacement can have positive benefits for youth's adult outcomes.

The analysis reveals that children displaced by public housing demolition have notably better labor market outcomes measured in early adulthood compared with their non-displaced peers. Additionally, there seem to be positive impacts on criminal and schooling outcomes for relocated youth as well, shown through a decrease in arrest rates for violent crime and a reduced likelihood of dropping out of high school. In terms of housing policy, this paper demonstrates that relocation of low-income families from distressed public housing can have substantial benefits for children of any age.

To read the full paper in the American Economic Review:

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20161352

Dr. Eric Chyn speaking on neighborhood effects:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rkvqBeIRu6Y&ab_channel=hceconomics

For additional literature on the economics of relocation:

"The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment," Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Lawrence F. Katz, 2016: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20150572

"Achieving Escape Velocity: Neighborhood and School Interventions to Reduce Persistent Inequality," Roland G. Fryer Jr., Lawrence F. Katz, 2013: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.103.3.232